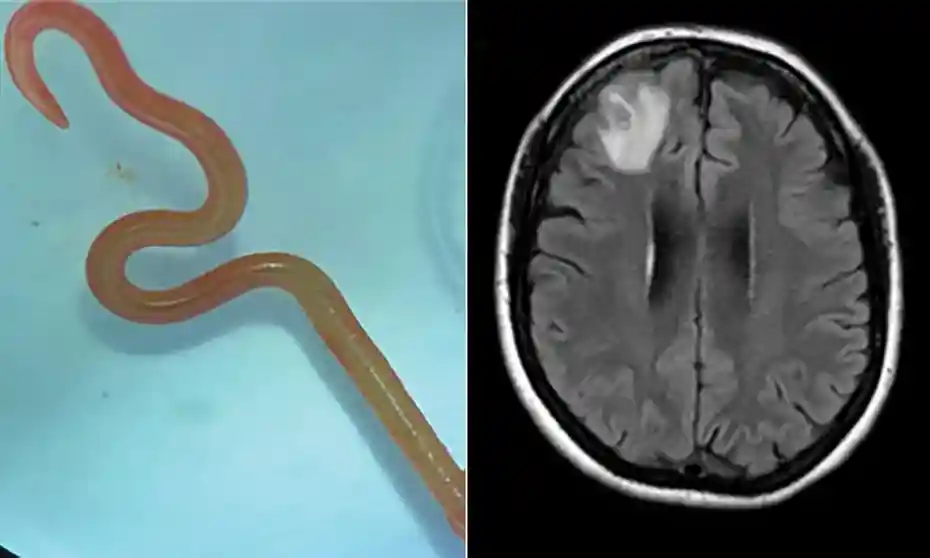

- Before doctors removed an 8 cm roundworm often found in pythons, a woman complained of forgetfulness and despair.

Dr. Sanjaya Senanayake, a specialist in infectious diseases at Canberra Hospital, was having a fairly routine day on the ward when a neurosurgeon colleague called and said: “Oh my god, you wouldn’t believe what I just found in this lady’s brain — and it’s alive and wriggling.”

Dr. Hari Priya Bandi, a neurosurgeon, called Senanayake and other medical staff members for advise on what to do next after discovering an 8 cm long parasitic roundworm in her patient.

The patient, a 64-year-old lady from south-eastern New South Wales, was initially admitted to her local hospital in late January 2021 after experiencing gastrointestinal pain and diarrhoea for three weeks, followed by a persistent dry cough, a fever, and night sweats.

Her symptoms expanded to include despair and amnesia by 2022, which led to a referral to a hospital in Canberra. Her brain underwent an MRI scan, which revealed anomalies that required surgery.

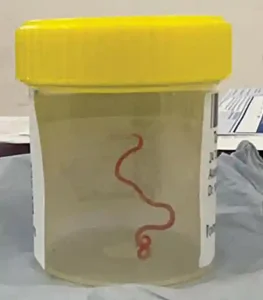

The specimen of a roundworm that was extracted from the woman’s brain. Photograph: Canberra Health

Senanayake argued that the neurosurgeon “definitely didn’t go in there thinking they would find a wriggling worm.” “While neurosurgeons frequently treat brain infections, this was a once-in-a-career discovery. Nobody anticipated discovering that.

A team at the hospital rapidly came together in response to the unexpected finding to determine what sort of roundworm it was and, more crucially, to determine whether the patient would need any additional treatment. Senanayake said, “We simply went for the textbooks, looking up all the different types of roundworm that could cause neurological invasion and disease.” After failing to find anything, they sought assistance from outside specialists.

Canberra is a tiny city, therefore Senanayake explained that the worm, which was still living, was sent right to the CSIRO scientist’s lab who has a lot of experience studying parasites. He simply gave it a quick glance before exclaiming, “Oh my goodness, this is Ophidascaris robertsi.”

The roundworm Ophidascaris robertsi is typically seen in pythons. The patient in the hospital in Canberra is a first-ever discovery of the parasite being found in humans.

The patient lives close to a lake where carpet pythons live. Although she had no direct encounters with snakes, Senanayake claimed that she frequently picked local grasses from the area of the lake, particularly warrigal greens, for use in cooking.

The medical professionals and researchers working on her case speculate that a python may have released the parasite into the grass through its faeces. They surmise that the patient contracted the parasite either after eating the greens or after touching the native grass and transferring the eggs to food or kitchen utensils.

According to Senanayake, a specialist in infectious illnesses based at the Australian National University, the patient needed to be treated for any more larvae that may have infected other organs like the liver. Care was taken, nevertheless, as no patient had ever had the parasite treated previously. As the larvae died out, some drugs, for example, could cause inflammation. They also needed to take drugs to prevent any potentially negative side effects because inflammation can be detrimental to organs including the brain.

The most typical host for Ophidascaris robertsi is a carpet python. Featured Image: Dan Himbrechts/AAP

Senanayake praised the patient, saying, “That poor patient, she was so brave and wonderful.” “We really take our heads off to her because you don’t want to be the first patient in the world with a roundworm discovered in pythons. She has been fantastic.

The patient is doing well, according to Senanayake, and is still under constant observation. The notion that the patient’s immunocompromised state from a prior medical issue may have aided the larvae taking hold is being investigated by researchers.

The incident was covered in the September issue of the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases. According to the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, animals are the primary source of three-quarters of new or emerging infectious illnesses that threaten humans.

Senanayake noted that as people and animals begin to coexist more intimately and their ecosystems begin to overlap more, the risk of diseases and infections spreading from animals to humans is underscored by this world-first case.

“In the past 30 years, there have been about 30 new infections worldwide,” he stated.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/aug/17/flesh-eating-bacteria-deaths-new-york-Connecticut

About 75% of newly developing illnesses worldwide are zoonotic, which means they have spread from animals to people. It also covers coronaviruses.

Since the Ophidascaris infection is not contagious, this patient’s illness won’t result in a pandemic like the Covid-19 or Ebola epidemics. However, since the snake and parasite are widespread around the world, it is conceivable that more cases may be identified in other nations in the years to come.

Prof. Peter Collignon, a specialist in infectious diseases who was not involved in the patient’s case, stated that some zoonotic disease cases may never be discovered if they are rare and doctors are unsure of what to look for.

He stated that “sometimes, the cause of a death is never discovered.”

It’s important to exercise caution while interacting with animals and the environment, he said, washing your hands frequently, cooking your food properly, and wearing protective clothing, such as long sleeves, to avoid getting bitten.

Source:TheGuardian